In order to ban someone, the employee must give only one verbal warning to stop the behavior before being empowered to ban the alleged perpetrator. In effect, a city employee could have someone banned from all public Prineville spaces for having a dog that disturbs any person by frequent or prolonged noise (aka barking).

During the hearing in which this ordinance was approved (public comment was not required by law), the Chief of Police, Dale Cummins, said part of the purpose of the ordinance is to be an educational tool, part of it is to be a warning tool. It is unclear what educational value is being added to public spaces. This is another enforcement tool for unjust laws already in existence.

During the hearing, Cummins addressed concerns that this ordinance was to target houseless people living outside by saying: “If I wanted to target the homeless, I could do it with laws that are on the books right now.”

Cummins further stated that the ordinance was not intended to be punitive or “a stick,” but later rationalized the ordinance by saying that “If someone uses heroin in a park, I can certainly arrest them for that, but they could be back in the park 30 minutes later.”

We know that people use heroin in private places, and those with the privilege of an indoor setting to use drugs are not subject to this exclusion from public space. If you don’t have a private space and aren’t allowed in Prineville’s public spaces, then the effect is punitive, even if the stated intent is not.

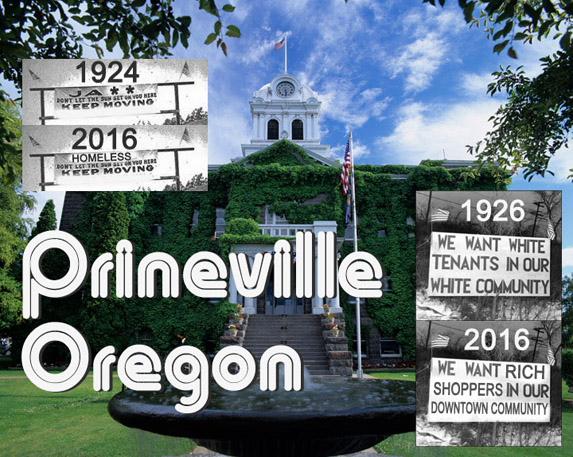

The exclusion ordinance falls in line with a long history of classism and racism in Oregon—denying people of color and poor people the right to exist in public spaces.

Our society at-large’s historic amnesia means that too many have forgotten that when Oregon was granted statehood in 1859, it was the only state in the Union with a Constitution that forbade black people from living, working, or owning property here.

Oregon’s racial exclusion laws made it illegal for black people to move to the state as late as 1926. And the Fourteenth Amendment, which gives everyone equal protection under the law and was written intending to give former slaves equal citizenship status, was not ratified in Oregon until 1973.

These laws echo Sundown Laws, Jim Crow Laws, Ugly Laws, Anti-Okie Laws, and other laws which disproportionately affect people who are least valued by capitalism. These laws all deny people the right to exist in or use public spaces based on their identities.

The effect of these laws is seen still today in Oregon, one of the top 10 states disproportionately imprisoning Black people. People of color are disproportionately unhoused and poor, so to naively assume that a law impacting public space use would not impact unhoused and therefore black/brown people disproportionately would be a willful denial of reality.

Prineville has now cemented itself as a part of Oregon’s continued legacy of violating the human rights of poor, black, and brown people. Kudos, Prineville.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.