Originally Post at Stop the Sweeps PDX

Portland’s camping ban has been on the books for over four decades with devastating impacts on homeless people trying to survive.

The camping ban has also faced numerous legal challenges and plenty of protests among homeless people and housed neighbors.

Cities, like Portland, use camping bans to make homeless people disappear without doing anything to actually solve the housing crisis which made homelessness so visible in the first place.

Understanding this history is essential to understanding the current policies in regards to sweeps and recent efforts to ramp up enforcement of the camping ban. Better yet, it can help provide us a vision and roadmap to a future where we can finally put an end to the sweeps and have housing for all.

Early History of Portland’s Camping Ban

Portland’s camping ban has its roots in the early 1980s. The law was created under the leadership of Mayor Frank Ivancie.

Mayor Ivancie, who was in office from 1980 to 1985, had a reputation for ‘law and order’. He was a staunch supporter of President Ronald Reagan, which was deeply reflected in the policies he enacted.

After his death in 2019, The Oregonian reflected on his legacy; calling him the last “conservative mayor of Portland”. Ivancie’s legacy includes blatant cruelty towards homeless people.

Ivancie opposed the construction of Pioneer Courthouse Square, saying it would attract homeless people (he wanted to charge a fee for entry to the square). – excerpt from The Oregonian

Mayor Ivancie waged what he called a ‘war on crime’ in the early 1980s. He pushed forward several ‘anti-crime ordinances’, despite the city attorney advising him that many of them were unconstitutional.

A large chunk of these ‘anti-crime ordinances’ were enacted under Title 14 “Public Peace, Safety, and Morals”. There were 19 ordinances enacted under Title 14 during Frank Ivancie’s tenure as mayor.

The camping ban was officially adopted on June 2nd, 1981. It passed with a 3-1 vote. Commissioner Margaret Strachan was the lone dissenting vote.

Mayor Ivancie’s ‘war on crime’ and the ensuing camping ban was a testament to the growing threat of neoliberalism that was quickly becoming a worldwide phenomenon. Portland was certainly not immune.

Neoliberalism and the Advent of Modern Homelessness

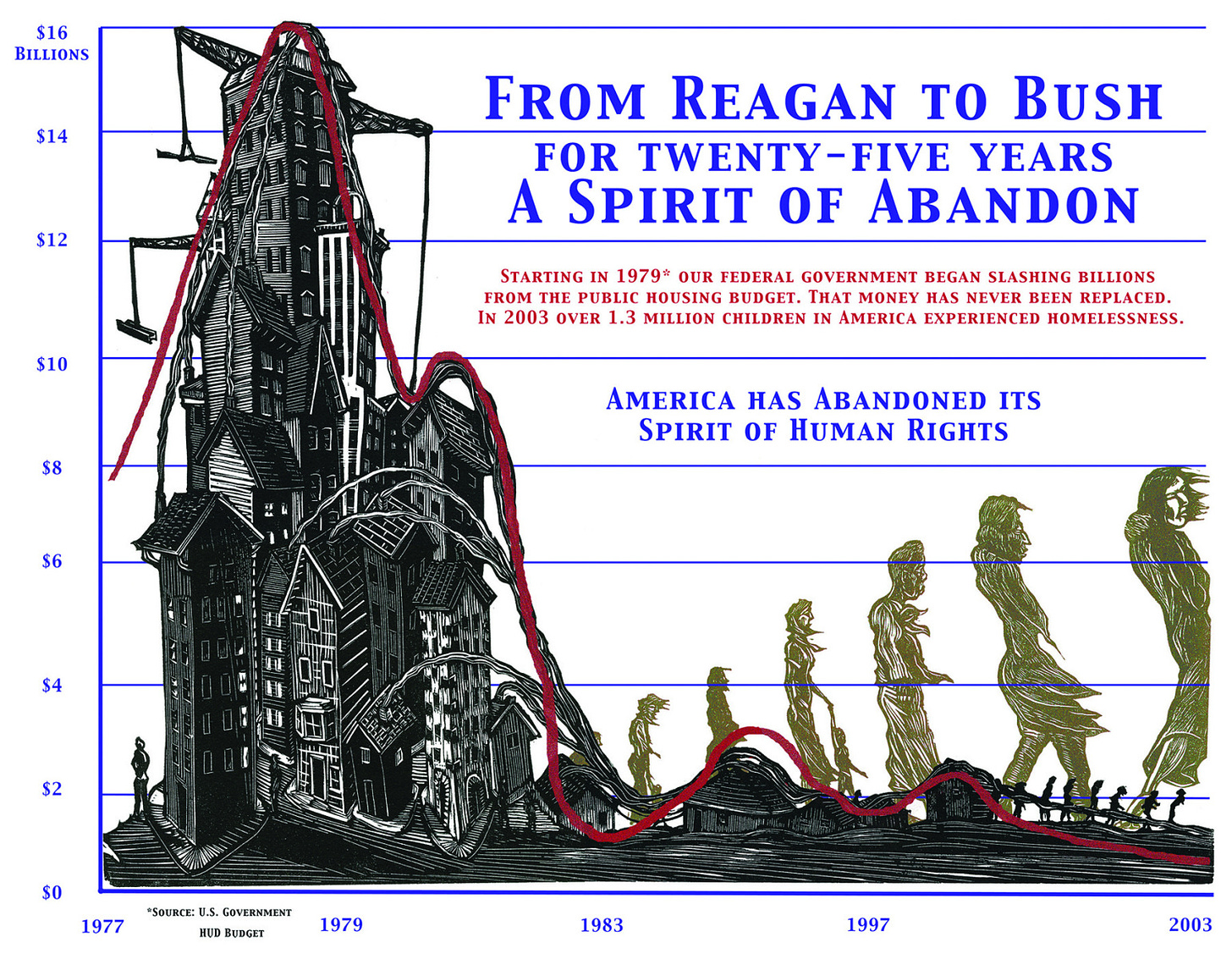

The rise of rampant neoliberalism during the 1980s coincided with the advent of modern day homelessness. Neoliberalism is a political movement which favors privatization and minimal government intervention on social welfare.

Homelessness is not new, per se, but the way in which it manifests today is a direct result of neoliberal policies enacted in the early 1980s. Most notably, the disinvestment and dismantling of federal public housing, spear-headed by the Reagan administration.

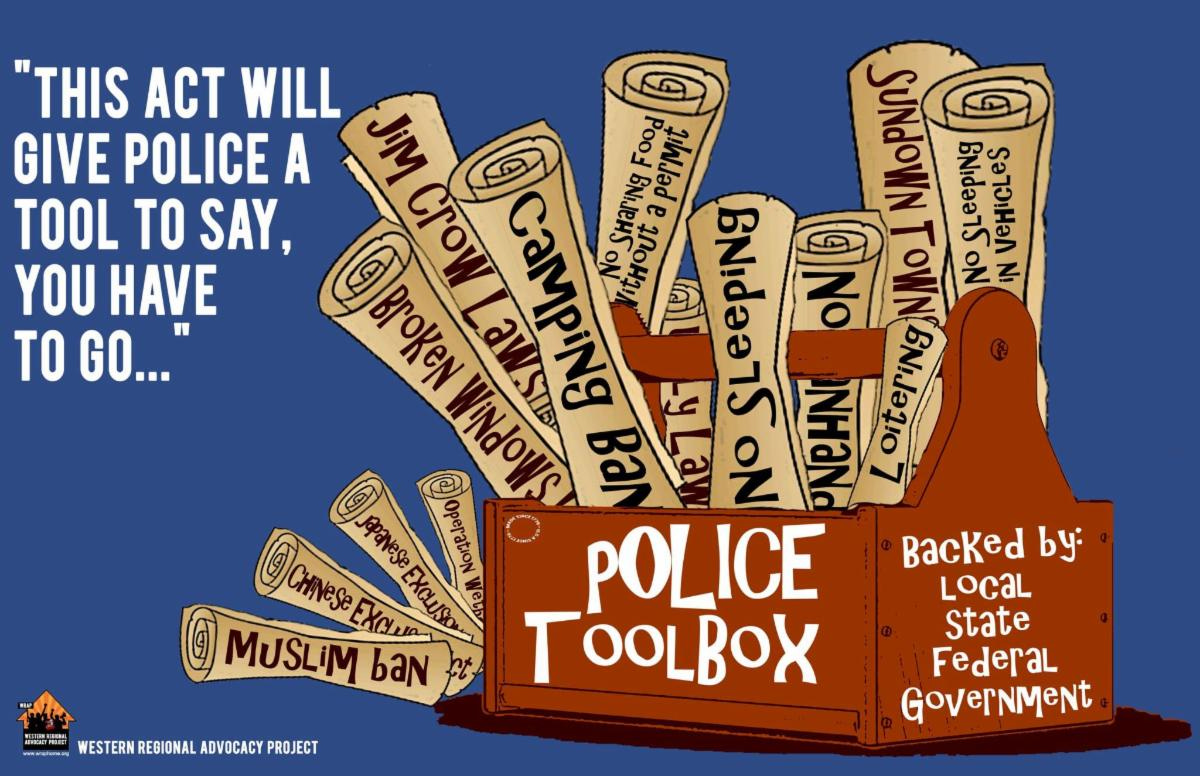

Neoliberalism also encouraged the privatization of public space. Public sidewalks, parks, and gathering spaces were increasingly oriented towards encouraging economic activity. As a result, there was a large push to exclude poor and homeless people from public space. In order to do that, cities began enacting several laws criminalizing homelessness and poverty, such as camping bans.

Without Housing, a report published by Western Regional Advocacy Project (WRAP), is a great resource to learn more about the origins of contemporary mass homelessness

Anderson Agreement

After almost three decades of Portland’s camping ban wreaking havoc, six homeless people banded together and filed a class action lawsuit against the City of Portland.

The lawsuit asserted the practice of issuing citations and arresting homeless people for camping and sleeping in public is cruel and unusual punishment, a violation of the Eighth Amendment. The lawsuit also asserted the ordinances violate the Fourteenth Amendment by restricting the ability for homeless people to travel and have freedom of movement.

On July 30th, 2009, a district court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs affirming their claim that the ordinances are a violation of the Eighth Amendment. However, the court denied the claim that the ordinances were in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

A settlement agreement was finalized on June 7th, 2012, colloquially known as The Anderson Agreement, which requires the City of Portland to give at least 24 hour notice before removing a camp (i.e. sweeping).

Mind you, this was already required by state law: ORS 203.077 and ORS 203.079. The Anderson Agreement merely placed extra pressure on the city to obey the law. Failure to comply now opens the city up to more, costly litigation.

Despite a few small reforms, the lawsuit ultimately did not result in the overturning of the city’s camping ban, to the disappointment of plaintiffs.

In addition to the new guidelines regarding how the camping ban is enforced, the lawsuit also resulted in a small monetary settlement for each of the plaintiffs. One of the plaintiffs, Leo Rhodes, gave his money back to the community:

“All my money is going toward Right 2 Dream Too… Because this is giving them a place to go — some stability and some sanity. Where they can have a safety zone.” – Leo Rhodes as quoted in Street Roots

This is a protest, not a camp

Resistance against Portland’s camping ban extends much further than that of lawsuits. Litigation is a tool to fight against the criminalization of homelessness but it can only go so far. Portland has a rich history of protest that’s continued to this day.

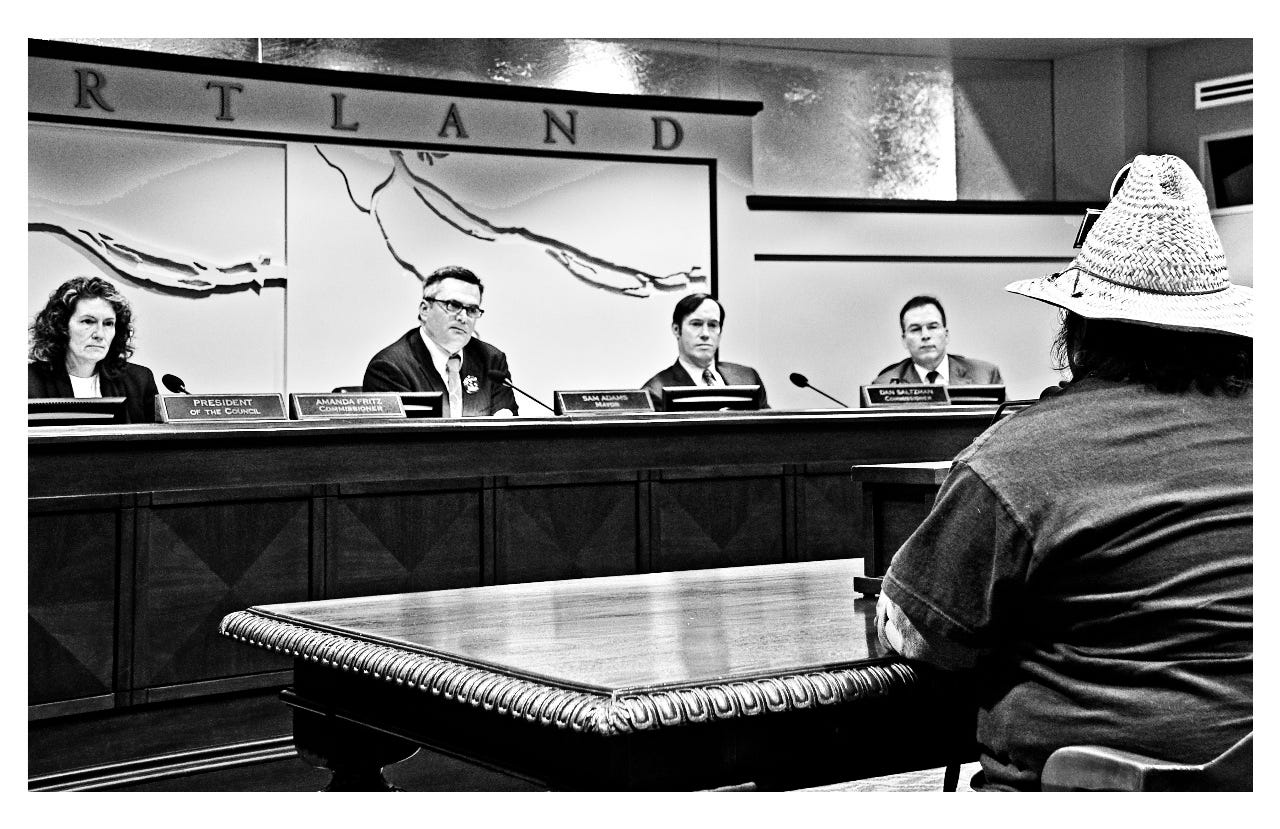

One such protest occurred in 2008 outside of Portland City Hall in protest of Portland’s camping ban.

The protest, at first an impromptu showing of five people displaced from under the Burnside Bridge by April’s campsite sweeps, swelled to include more than 100 homeless people and supporters. Their tarps, blankets and protest signs (“Housing is a human right”; “This is a protest, not a camp”) lined the edge of the sidewalk in front of City Hall. Street Roots, May 16th, 2008

The city wasted no time putting up postings declaring the protest an ‘illegal campground’. In response, organizers of the protest sent a letter to Mayor Tom Potter’s office requesting a meeting.

“We would like to invite you to have another conversation with us about the issues we are raising. We understand that you and other city officials are working to open additional shelter spaces. We appreciate your efforts but we want to talk about where those who cannot get into a shelter are supposed to go. We want to discuss how we can be involved in reducing homelessness in our city. In short, we want a real dialogue about the issues of homelessness and affordable housing.” — Excerpt from letter sent to Mayor Tom Potter

Mayor Tom Potter ultimately agreed to meet with some of the protesters. The activists pushed the mayor’s office to consider repealing the camping ban and sit-lie ordinances. However, the mayor’s office rebuffed this request and said they had a ten year plan to end homelessness (spoiler alert: that planned failed).

“Do you know how tired we are? You can’t sit here, you can’t stand here, you can’t lie here. You can’t cover up, you can’t sleep. You can’t get any rest. We’re midnight nomads, walking around with all our gear on our back, being told that we can’t sleep.” – Quote from activist Larry Reynolds in Street Roots

The protest outside of City Hall lasted for nearly three weeks before police shut it down arresting seven people.

Carrying the past into present day

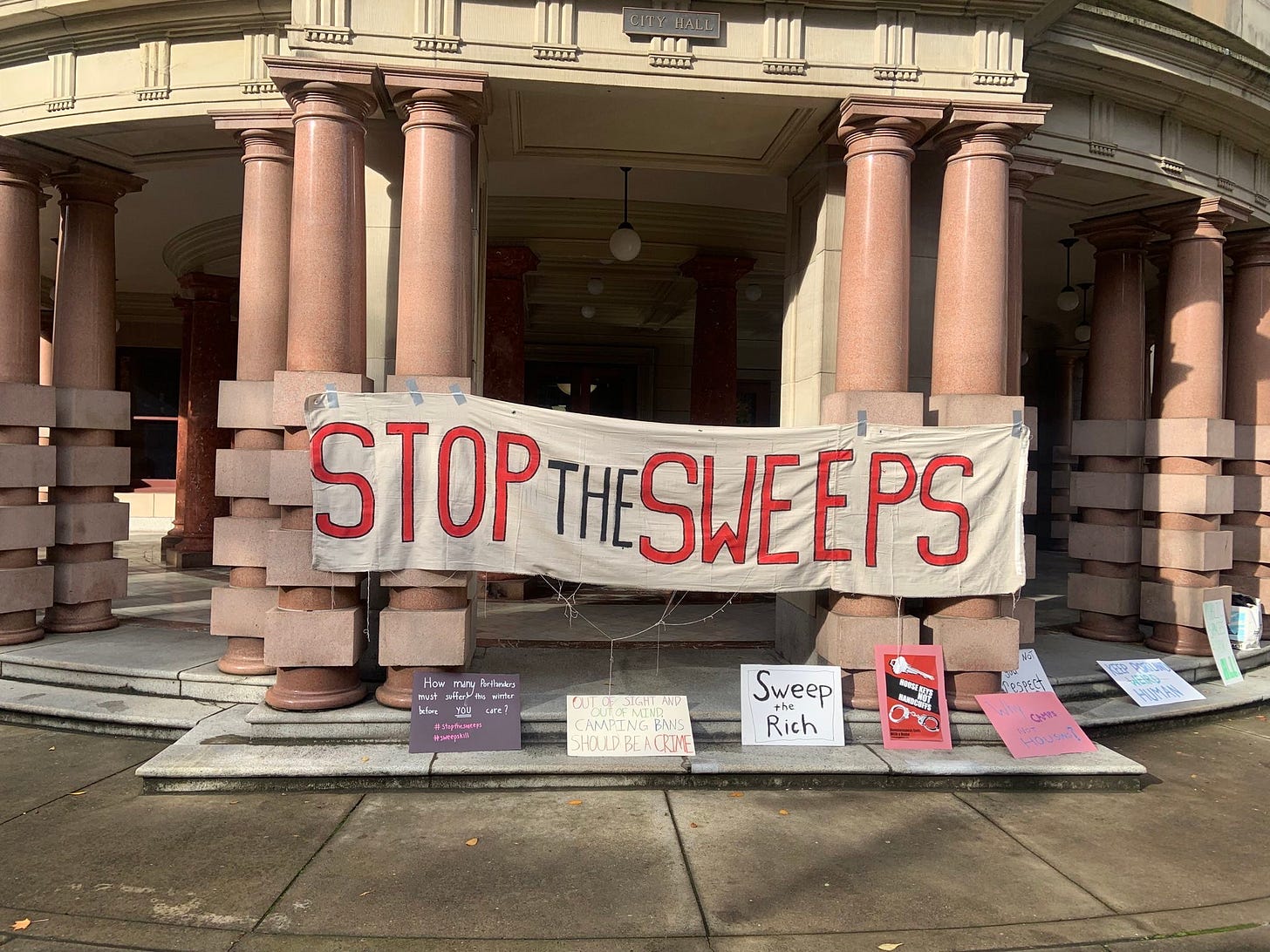

In late months of 2023, a new set of people once again camped outside of City Hall to protest the newest iteration of Portland’s camping ban. The protest camp started after a rally outside City Hall.

What started with just a few people and tents quickly grew with tents lining the entire street outside of City Hall. We had a banner facing traffic that read ‘stop the sweeps’. Posters, art, and signs were scattered amongst the trees, tents, and tables.

We had a ‘living room’ where people hung out during the day, ate food, and chatted with passerby’s. It was where we facilitated our first camp meeting. Planting the seeds for what future actions could look like.

The protest lasted just over a month before the City posted us for a sweep. Despite indicating, much like the protesters in 2008, that “this is a protest, not a camp”, the sweep persisted. The protest may have been over but the fight was far from it.

As much as they try to sweep us all under the rug, we will keep coming back as long as these injustices continue to exist.

Portland Police Bureau Directives

Portland’s camping ban policy involves more than what is written in the camping ban ordinance. Enforcement of the camping ban is dictated through police directives.

Portland Police Bureau (PPB) issued directive 0835.20 Managing Public Spaces in 2001. The directive stated PPB must give a 24 hour notice before enforcing the camping ban.

The directive included two major exceptions to the 24 hour notice; allowing police officers to enforce the camping ban and sweep people without notice:

- Camps on private or state owned property

- Camps where illegal activity or emergencies are occurring (which of course is up to the discretion of the cops)

As was evident from the Anderson lawsuit, police swept people and enforced the camping ban often and without notice. The ‘exceptions’ laid out in the police directive was one of the many tools they used to justify continued harassment and displacement.

The directive was amended in 2008 with more exceptions. This time the camping ban could be enforced in public parks without notice. They also defined ‘permanent postings and signs prohibiting camping as providing sufficient notice before a sweep’. Camps that are deemed ‘non-established’ can also be swept without notice.

The new directive was issued during the ongoing Anderson lawsuit, which resulted in major backlash from homeless advocates and legal experts.

Ultimately, as a result of the Anderson Agreement, PPB was required to once again revise the directive with stricter protocol regarding 24 hour notices; thus making it more difficult to exploit the myriad of legal loopholes they had used in years prior.

Most recently, in 2015, the directive was updated to clarify that PPB is only to provide a support role during sweeps. This is because of the creation of the Homelessness and Urban Camping Impact Reduction Program, which replaced police as the primary entity in charge of sweeps.

The directive is set for its next review on August 4th, 2024.

Martin v. City of Boise

In 2009, a lawsuit was filed on behalf of six homeless people in Boise, Idaho arguing the city’s camping ban and ban on sleeping in public are unconstitutional.

In 2018, after almost ten years of litigation and appeals, the Ninth Circuit issued the landmark decision in Martin v. City of Boise:

Ordinances that ban camping and sleeping in public without adequate shelter alternatives are a form of cruel and unusual punishment, thus a violation of the Eighth Amendment.

As a result of this ruling, the decision not only impacted the City of Boise, it now applied to all cities who fall under the jurisdiction of the Ninth Circuit. Oregon, and subsequently the City of Portland, were now forced to comply with the ruling.

Martin v. Boise certainly didn’t end criminalization of homelessness. The case only applied to two specific ordinances: camping bans and bans on sleeping in public. To bypass the ruling, many jurisdictions have simply used different ordinances to continue harassing, citing, and arresting homeless people.

Upon the decision’s announcement, both the mayor and police asserted the ruling had little impact on Portland because they had already begun phasing out the camping ban.

“We don’t issue citations for being homeless… We don’t arrest people for homelessness… There is no code, there is no law that makes homelessness a crime in the city of Portland.” – Mayor Ted Wheeler during a press conference following the Martin decision

Despite these assertions, arrest data from 2017 revealed over half of arrests in Portland were of homeless people. Many of the arrests were for charges such as trespassing, disorderly conduct, offensive littering; laws that are predominantly used against homeless people specifically.

Martin v Boise does not prevent cities from conducting sweeps but it does prevent cities from citing and arresting people for camping under most circumstances.

Johnson v. Grants Pass and the future of Martin v. Boise

A new lawsuit, filed in 2018, Johnson v. Grants Pass built upon the precedent set in Martin v. Boise.

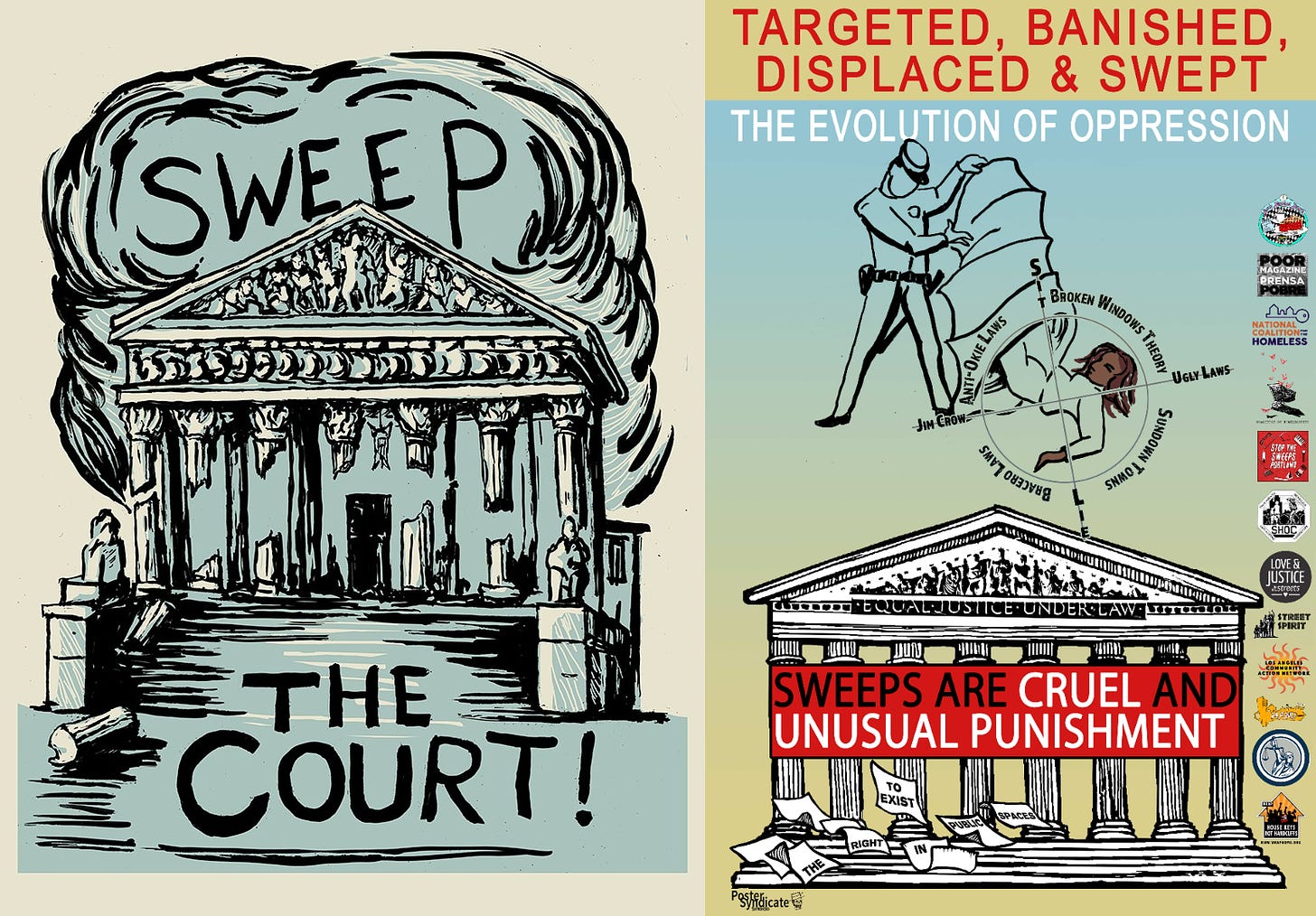

This time, however, the case was appealed all the way to the Supreme Court. This could result in the unraveling of years of case law, allowing local jurisdictions to resume enforcement of camping bans. This case will have a major impact on the future of Portland’s camping ban.

Oral arguments in front of the Supreme Court are scheduled for April 22nd and a final decision is expected sometime during the summer months of 2024.

Legal Loopholes – HB 3115

HB 3115, a bill introduced in 2021, required all cities in the State of Oregon to revise their anti-camping ordinances to ensure the restrictions are ‘objectively reasonable’ regarding ‘time, place, and manner’.

This vague language left a lot of leeway for cities to argue their camping bans were ‘objectively reasonable’. Effectively, this bill did little to change the status quo despite being touted as a bill to ‘decriminalize homelessness’. Proponents of the bill described it as a means to codify Martin v. Boise into law.

Both Martin v. Boise and Johnson v. Grants Pass asserted cities can implement some restrictions in regards to ‘time, place, and manner’ when governing public space.

In other words, a total ban on camping is unconstitutional but regulating when, where, and how people camp is still allowed as long as it is ‘reasonable’.

This interpretation of the case law provided an opportunity for local jurisdictions to find loopholes that allow the continued enforcement of camping bans.

This was almost certainly the intended goal of HB 3115: to pave the way for local jurisdictions in Oregon to continue enforcement of their camping bans with the least amount of risk for potential lawsuits. It’s almost as if a bunch a Oregon mayors got together and drafted a policy to help them make this a reality…. oh wait, that’s kind of exactly what happened!

The bill was pushed forward by the League of Oregon Cities, a lobbying organization that consists of elected leaders across Oregon; leaders who have a vested (and monied) interest in maintaining the status quo.

It’s worth noting the League of Oregon Cities filed an amicus brief to the Supreme Court in support of Grants Pass (i.e. overturning Martin v. Boise).

So it’s pretty fucking obvious what the real intention behind HB 3115 was. It wasn’t a bill to ‘codify Martin v. Boise into state law’ and it most definitely wasn’t a bill to ‘decriminalize homelessness’.

Right to Rest Act

While state representatives were patting themselves on the back about making progress towards ‘decriminalizing homelessness’, they were also working behind the scenes to kill a bill that would’ve actually made tangible steps to decriminalize homelessness: Right to Rest Act.

The Right to Rest Act would protect homeless people from discriminatory enforcement of laws that prevent rest. Specifically, prohibiting cities from citing and arresting homeless people for exercising the following rights:

- To occupy and move freely in public space

- To rest (sit, stand, and sleep)

- To eat and share food

- To occupy a legally parked vehicle

The law would also guarantee legal and civil defense for anyone who faces charges for the above rights, known as the ‘Homeless Bill of Rights’.

Right to Rest was drafted in response to street outreach surveys conducted by members of Western Regional Advocacy Project (WRAP). The bill was a grassroots effort coming from the people who are most directly affected versus the lobbying interests of city governments and business interests that heavily influenced the drafting of HB 3115.

In Oregon, of the over 565 homeless people surveyed 94% they were harassed for sleeping in public with 51% of people receiving citations.

“You are out here by yourself. When you finally get away from downtown and the police harassing you, you then have to worry about other people. And if you got pushed far enough out, you’d have to worry about cougars.” – excerpt from an interview with Cara from ACLU’s report, Decriminalizing Homelessness: Why Right to Rest legislation is the high road for Oregon

Despite all of the grassroots support, with dozens of people lined up to testify in support, the hearing for Right to Rest was cut short in favor of HB 3115.

The bill was abruptly pulled off the agenda entirely by committee chair, Janelle Bynum. It was only put back on the agenda after outrage from advocates and inquiries by journalists. Ultimately, the ‘public hearing’ was scheduled for a measly 15 minutes. As if that wasn’t bad enough, the testimony was cut off after only 7 minutes. Only three people were able to testify.

“Community members fought to get the hearing rescheduled, and once it was rescheduled, they had to scramble to coordinate resources in order to make the hearing accessible for those without internet or computer access. This was made more difficult given that we weren’t able to clarify with any certainty what the new hearing process would look like or why it was changed so suddenly in the first place. What may seem like small procedural tweaks ultimately amount to the reinforcement of historical inequities in which only the wealthy and powerful (read: white) can engage with their government in a meaningful way.” – statement from WRAP organizers in the aftermath of the Right to Rest hearing

Portland’s Daytime Camping Ban

All cities in the State of Oregon were required to revise their anti-camping ordinance in order to come into compliance with HB 3115 by July 2023.

Portland amended the camping ban with new ‘time, place, and manner’ restrictions that are ‘objectively reasonable’ (or at least ‘reasonable’ in the eyes of the City Attorney’s Office).

Time restrictions: The new ordinance declared camping on public property is only allowed between the hours of 8pm-8am. Doesn’t matter if you have mobility issues. Doesn’t matter if you have nowhere else to go during the daytime. Doesn’t matter if you work at night and need to sleep during the day.

Place restrictions: There is a list of places you are never allowed to camp, encompassing large swaths of the city, and zero guidance regarding where you are legally allowed to sleep.

Manner restrictions: Lastly, there is a lengthy list of prohibited activities, many of which impede the ability to engage in basic survival activities.

It should go without saying… None of these restrictions are even close to being objectively reasonable!

Passage of the ordinance and ensuing fall out

Portland City Council voted to approve the new camping ban on June 7th 2023 with a 3-1 vote. Commissioner Carmen Rubio was the lone dissenting vote.

The ordinance was supposed to take effect in the fall of 2023; however, a new lawsuit, filed by Oregon Law Center prevented this from happening. The lawsuit resulted in a judge issuing a preliminary injunction. This means the ordinance cannot be enforced until the lawsuit is settled and/or the judge rescinds the injunction. The lawsuit is still ongoing as of March 2024 and may take a year or more before a final ruling is issued.

Most recently, Mayor Ted Wheeler indicated the ordinance may be scrapped and rewritten.

“We have already drafted and will shortly introduce a new ordinance… It won’t be as strong as the one we wanted, but we believe it will pass constitutional muster, although — small asterisk — they didn’t really give us any guidance, so we really don’t know.” – Mayor Ted Wheeler during a March 2024 press conference

History repeating

If you think this daytime camping ban sounds familiar you’d be right. In 2016, former Mayor Charlie Hales created a similar ordinance. This ordinance allowed camping on public property (that are not sidewalks) between 9pm and 7am.

At the time, anti-homeless groups and lobbyists were strongly opposed to this policy. A lawsuit, spearheaded by Portland Business Alliance (now Portland Metro Chamber), was filed against Mayor Hales challenging the ordinance. Ironic, considering, they were huge proponents of the current proposed daytime camping ban.

Ultimately, the ordinance was scrapped after six months. The announcement of this policy change coincided with a massive sweep of hundreds of homeless people along the Springwater Corridor.

The fight continues

The future of Portland’s camping ban is contingent on the outcomes of current lawsuits.

It is possible (and likely) the Supreme Court will rule in favor of Grants Pass, thus overturning Martin v. Boise. The Supreme Court’s ruling will also likely influence the lawsuit against Portland’s daytime camping ban.

Despite what seems like a grim future ahead of us, the fight will continue. The courts were not designed to bring us liberation. This fight doesn’t end at the whim of a judge’s pen. We must look beyond the (in)justice system, towards a future where people can live a dignified existence.

As the courts, politicians, and moneyed interests attempt to dehumanize us, may we continue to show humanity towards each other.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.